Por: Carlos Diaz (@CarlosDiazME)

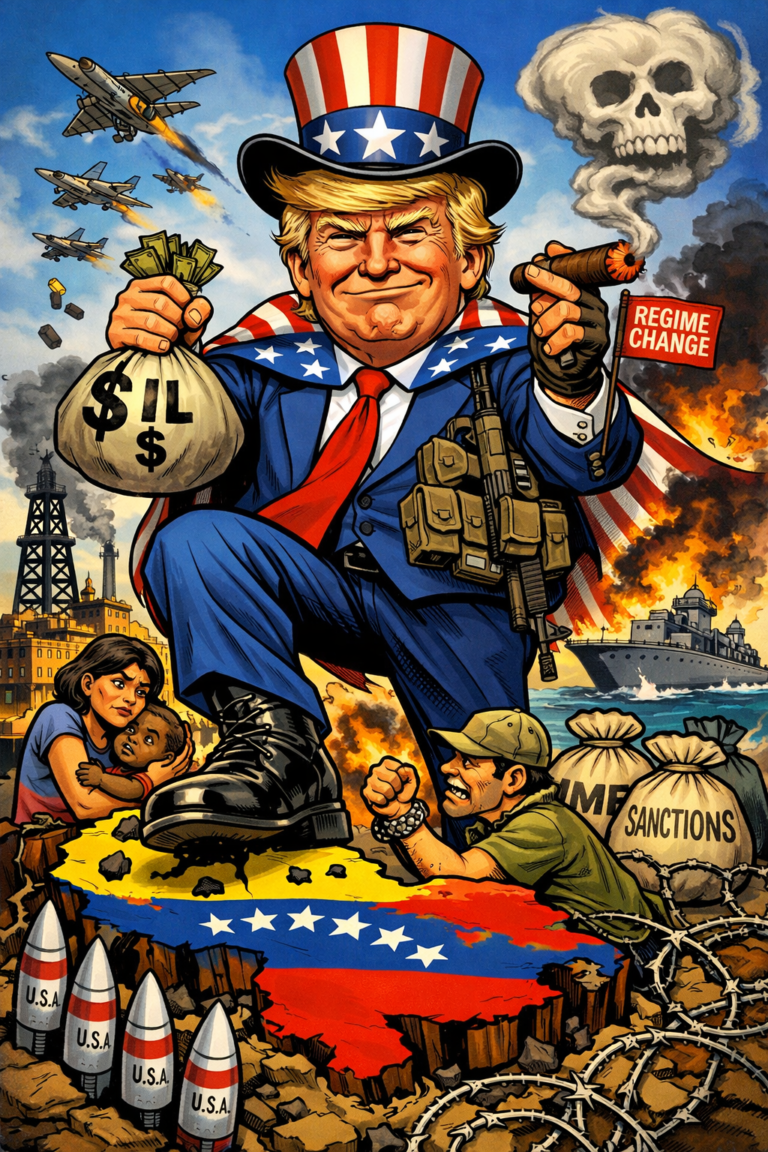

On January 3, 2026, a long-brewing rupture in the post–Second World War order became explicit when the United States launched a military operation in Venezuela and abducted President Nicolás Maduro. This moment is significant not only because it violates international law, but also because imperial intent was articulated with unprecedented clarity. For decades, the moralistic language of democracy, human rights, and humanitarianism shrouded U.S. interventions in the Global South, concealing their underlying logic of dominance. Trump’s intervention eliminated these covert tactics. Declaring that “very large oil companies” would rebuild Venezuela and profit from “our oil”, he spoke in the language of possession rather than partnership, marking a moment when the empire no longer felt obliged to justify itself ideologically.

This action is a result of structural pressures, not solely due to the actions of one individual. The decline of US economic dominance, the ever-growing US-China geopolitical competition and the historical subjugation of Latin America as an area of extraction and strategic control created a point of convergence for these structural forces. The Bolivarian movement had previously created a glimmer of hope around the globe for the left, until it began to unravel under the Maduro regime due to the combination of extreme dependence upon oil revenue, an inability to diversify the economy and a growing reliance upon military loyalty instead of popular consent, leading to a state of built-in vulnerability. This phenomenon is evidenced by Venezuela, a nation severely damaged by years of economic mismanagement, international sanctions and a continued decline in political legitimacy.

The dual reality of external assault and internal collapse presents a profound dilemma for the left. Opposing U.S. intervention is necessary, but doing so without analysing the internal limits of the Maduro regime risks reducing politics to reflexive allegiance. The arrest of Maduro did not signal the end of a revolutionary movement; instead, it represented a critical juncture, underscoring the intrinsic weaknesses of a system dependent on commodity booms and incapable of sustaining democratic or social authority in the face of evolving external conditions.

In this story of imperial aggression, we have to examine the audacious revival of the Monroe Doctrine, the material and geopolitical limits of oil as a source of revenue, the contrasting eras of Chávez and Maduro; and the structural collapse of the Venezuelan state and military. Above all, it argues that the left must respond with clarity: opposing imperialism while reconstructing social power, deepening participatory structures, and addressing the internal contradictions that have historically undermined sovereignty. Venezuela today is both a victim and a warning: a lesson in the dangers of dependence, the fragility of redistribution without structural transformation and the imperative for anti-imperialist strategy rooted in working-class power.

Trump-Era U.S. Imperialism

Donald Trump’s declaration that the United States would send oil companies to “fix” Venezuelan infrastructure and extract profits encapsulates more than rhetoric—it embodies a new phase of imperial governance where military might, corporate interests, and geopolitical ambition converge openly. The logic was straightforward: sovereignty is secondary to the imperatives of extraction and strategic control. In this, Trump did not depart from the historical pattern of U.S. imperialism; he simply stripped away the ideological veneer that traditionally accompanied it. This shift must be understood within the context of a changing global order. The United States, while still militarily dominant, is experiencing a strong challenge to its economic and technological supremacy. China is increasingly challenging trade and investment flows, undermining its industrial base, and straining traditional alliances. In this setting, coercion is replacing consent. The intervention in Venezuela illustrates this transition: the empire is now less focused on fostering cooperation or leveraging local proxies and more intent on ensuring compliance through the direct application of force. The phrase “our oil” shows not only arrogance but also an awareness of structural insecurity. Imperial power no longer trusts global norms, multilateral institutions, or ideological persuasion to get what it wants. Behind this posture stands a recognisable social bloc: energy capital intent on securing reserves, defence corporations dependent on continuous conflict, and logistics and construction firms, for whom occupation itself becomes a field of accumulation.

By framing the intervention as a business operation, Trump collapsed the traditional divide between violence and profit. Military occupation, infrastructure reconstruction, and resource extraction are no longer separate domains—they are integrated instruments of accumulation. Such an arrangement represents a departure from the versions of imperialism, which relied on proxy governments, economic coercion and conditional aid. Now, the United States openly entertains the direct management of foreign territory, treating the Venezuelan state not as a sovereign partner but as a resource to be appropriated. Military-backed corporate operations render local political actors, previously considered indispensable intermediaries, optional.

Yet the intervention is not only about immediate extraction. It serves as a demonstration of imperial capacity, designed to send a warning to the region: defiance of U.S. interests will be met with coercion, not negotiation. Venezuela functions as a laboratory for a new hemispheric order, where sovereignty is conditional and resistance is criminalised. The structural logic behind Trump’s posture also reflects internal pressures within the U.S. capitalist system. Slowing global growth, market volatility, and intensified competition for energy resources create incentives for direct appropriation. Military force becomes a tool for securing assets that cannot be reliably obtained through trade or diplomacy. Yet this strategy is inherently unstable: occupation can provoke resistance, administrative overreach can inflate costs, and reliance on coercion undermines the legitimacy necessary for long-term control. The Venezuelan case thus exposes a fundamental tension in contemporary imperialism: capacity for force exists, but the capacity for sustainable governance is limited. Imperial rhetoric presents simplicity, but material and political realities remain complex and costly.

Revival of the Monroe Doctrine

The intervention in Venezuela on January 3 is not an isolated act of aggression; it is the actual revival of a doctrine that has shaped U.S.–Latin American relations for more than 200 years: the Monroe Doctrine. Articulated in 1823, it positioned the Western Hemisphere as a U.S.-protected sphere, warning European powers against intervention. Historically, it functioned less as a legal principle than as a strategic claim: Latin America was to remain subordinated to U.S. geopolitical and economic interests. Under Trump, this doctrine has resurfaced with unprecedented bluntness, stripped even of the veiled language of diplomacy, multilateralism, or ideological pretext.

For most of its history, the Monroe Doctrine operated indirectly. Coups, covert operations, economic pressure, and proxy regimes allowed Washington to dominate regional politics while preserving the formal appearance of sovereignty. During the Cold War, support for military dictatorships, conditional aid, and covert sabotage enabled efficient control, often framed in moralistic terms—from anti-communism to the defence of democracy. Sovereignty was nominally respected while materially hollowed out.

Trump’s intervention in Venezuela marks a decisive break from this indirect model. His National Security Doctrine explicitly frames the hemisphere as a U.S. sphere of influence, leaving no ambiguity about autonomy or external presence. The conditionality of sovereignty—previously masked by diplomatic language—is now openly codified: deviation from U.S. strategic or economic priorities is treated as hostility. Latin American states are no longer junior partners or managed allies; they are objects of enforcement, with political legitimacy contingent on compliance. The Monroe Doctrine thus shifts from a strategic warning to an operational blueprint for unilateral intervention.

Venezuela functions as the testing ground for this revived doctrine. The intervention demonstrates that defiance, even when articulated through popular sovereignty or anti-imperialist rhetoric, can trigger direct military and economic coercion. The objective is not merely regime change but precedent-setting: resistance invites occupation, resource seizure, and geopolitical subordination. The message to the region is clear—we will punish autonomous policies, diversified alliances, or independent economic strategies.

Several structural factors accelerate this shift. Expanding Chinese investment across Latin America—particularly in energy, infrastructure, and mining—has eroded the U.S.’s uncontested dominance. Even where such engagement remains limited in scale, its strategic significance is profound. The Trump administration interprets these footholds as challenges to hemispheric control, with Venezuela’s oil reserves and strategic location making it the primary site for forceful reassertion. The revived Monroe Doctrine is therefore both a continuation of historical domination and a response to intensifying global competition.

Unlike earlier periods, this revival carries no promise for development, modernisation, or regional integration. It is no longer framed as benevolent hegemony or pan-American cooperation but as coercion: compliance in exchange for protection, defiance in exchange for punishment. By discarding the ideological veneers of democracy, human rights, or anti-corruption, Trump’s doctrine exposes imperial power in its rawest form—territorial and resource domination enforced by military capacity.

The consequences extend well beyond Venezuela. Open coercion destabilises regional politics, militarises domestic governance, and renders institutions such as the Organization of American States largely irrelevant. Even compliant elites recognise the danger: a hemisphere governed by force alone is inherently unstable, prone to cycles of resentment, unrest, and conflict. At a global level, the message is clear—sovereignty is conditional, international law is subordinate to power, and imperial aggression is no longer exceptional but normalised. Venezuela is not an anomaly; it is a warning of a broader descent into unapologetic power politics.

Chávez era, Maduro era

A thorough understanding of Venezuela’s crisis requires distinguishing between two distinct historical periods: the Chávez era (1999–2013) and the Maduro era (2013–2026). Collapsing these periods into a single narrative obscures the material and structural conditions that made the Bolivarian project viable initially and explains why it became untenable under Maduro. This is not merely a question of personal leadership or political competence, but of economic foundations, social legitimacy, and institutional resilience.

Under Hugo Chávez, Venezuela benefited from a historically exceptional conjuncture. The global commodity supercycle of the 2000s, driven in large part by Chinese demand for oil, pushed prices to unprecedented heights. For an economy overwhelmingly dependent on petroleum exports, this generated a massive inflow of rents. Chávez used these resources to finance expansive social programs: subsidies for housing, healthcare, and education, wage increases, and programs aimed at empowering the historically marginalised. These policies materially improved the lives of millions, anchoring the Bolivarian project in genuine popular support. The working class and poor were not merely passive recipients but participants in a broader project of social redistribution, creating a coalition that gave Chávez significant legitimacy.

Yet even at its peak, Chávez’s model rested on a fragile foundation. Redistribution was almost entirely dependent on oil rents, while the underlying economic structure remained largely untransformed. Non-oil sectors remained underdeveloped, productive diversification was minimal, and private capital retained control over most production. The state functioned primarily as a distributor of oil wealth rather than a planner or regulator of long-term investment. This meant that the system’s stability was contingent on sustained high oil prices and continued access to rents—conditions external to domestic political action.

The death of Chávez in 2013 coincided with a collapse in global oil prices, exposing the fragility of the rent-based model. Nicolás Maduro inherited not only a deteriorating economic situation but also a political apparatus dependent on continuous redistribution to maintain legitimacy. Unlike Chávez, Maduro faced structural constraints that severely limited his policy options. The social coalition that had supported the Bolivarian project was increasingly disillusioned as living standards declined, hyperinflation eroded wages, and shortages became widespread.

Maduro’s response marked a qualitative departure from Chávez’s approach. Rather than reconstructing popular participation or transforming the productive base, the state increasingly relied on coercion and administrative control. The military became central to regime survival, enjoying economic privileges, access to subsidised goods, and control over lucrative sectors. The broader working-class base, once empowered and politically engaged, was marginalised, with social programs functioning more as mechanisms of political compliance than as instruments of empowerment. In effect, Maduro substituted class-based support with military loyalty, hollowing out the social and political foundations of the Bolivarian project.

This transformation had multiple consequences. First, it weakened the capacity of Venezuelan society to resist external aggression. In principle, a politically mobilised populace could serve as a check on imperialist encroachment, but Maduro had largely disengaged this social base. Second, it amplified internal contradictions: reliance on oil rents and military patronage left the economy and state vulnerable to shocks, whether from sanctions, price fluctuations, or foreign intervention. Third, it reinforced the corporatisation of the state, transforming institutions that had once facilitated popular participation into tools for managing scarcity and preserving elite control.

It is crucial to note that these internal failures do not absolve external aggression. U.S. intervention, sanctions, and geopolitical pressure compounded the crisis, but they did not create the structural fragility that allowed the Venezuelan state to collapse so rapidly. The Bolivarian system, built on oil rents and charismatic leadership, required continuous popular engagement and economic diversification—conditions that were weakened over time. The Maduro era shows that redistribution without change can’t keep legitimacy during a long-term crisis and that relying on narrow institutional mechanisms, like military loyalty, makes a country vulnerable to both internal collapse and external pressure.

In short, Chávez and Maduro governed under different structural and historical conditions. Chávez operated during a period of extraordinary resource inflows that allowed for meaningful, albeit temporary, redistribution and the construction of popular legitimacy. Maduro inherited a weakened economy, declining rents, and an eroded social base, leading to a reliance on coercion, bureaucratic control, and military patronage. The Bolivarian project’s collapse under Maduro was therefore not accidental; it was structurally produced, reflecting the perils of resource dependence, limited economic diversification, and the hollowing-out of popular power. Recognising this distinction is essential for understanding the Venezuelan crisis and for formulating strategies that link anti-imperialist struggle with the reconstruction of genuine social and political empowerment.

(This article was originally published on 11th issue of Hammer Magazine)

Editorial Board Member of Alternative Viewpoint