Until recently, the mention of ‘Manipur’ would evoke little more than images of Chitrangada and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose in the Bengali imagination. This perception shifted dramatically following Irom Sharmila Chanu’s prolonged, determined fast and the poignant march of the Manipuri mothers, which rattled our collective consciousness. Those with deeper cultural appreciation might recognise the name of internationally acclaimed theatre director Ratan Thiyam, who sadly passed away last July. However, many may be unaware that since May 2023, amidst the violent ethnic conflict that has engulfed Manipur, he has held both the central and state governments, as well as the Prime Minister, accountable for the situation and has persistently protested—going so far as to withdraw his name from the Peace Committee. Notably, the government had included him on the committee without his prior consent. Thiyam made it clear: “Unless the Centre takes greater interest, how can a Peace Committee here solve the problem?” He also raised the critical question, “Are we a part of India?”

We, for our part, know almost nothing about the history, conflicts, sufferings, and aspirations of Manipur—or of the other Northeastern states—much like we lack an answer to his question. Bengalis have been compelled to learn at least somewhat due to a history of undeniable cultural links. But what about the rest of India? What we do know is that if the ordinary people of Manipur were ever to demand full autonomy and seek separation from the Indian Union, we would—despite our ignorance—be quick to assert, ‘Manipur is an integral part of India.’

Let us now look back at what wounds have been inflicted on this “inseparable part” from May 2023 until February 2025, when President’s Rule was imposed.

May 2023 – February 2025

Over 285 people have been killed, predominantly from the Kuki–Zo community; the Meiteis, in contrast, have experienced fewer fatalities. Among the deceased are also security personnel.

Injured: Approximately 1,100

Displaced: Around 60,000

Destroyed: 4,786 houses and 386 places of worship, both Islamic and Christian. Consequently, the Kukis have been effectively eradicated from Imphal, while the Meiteis have been displaced from Churachandpur.

Schools?

The official statistics—which notably do not include information about schools—are merely a distorted reflection of reality. During my visit to Manipur last December, it became evident that the accounts of local residents do not align with the government’s figures. Furthermore, Greeshma Kuthar, Frontline’s exceptionally brave journalist, offers significantly different estimates based on her consistent reporting from the ground in Manipur. Her articles and podcasts offer credible information regarding the destruction of schools.

On 28 February 2025, President’s Rule was imposed. Yet, peace has not returned to Manipur. When has President’s Rule ever truly brought about peace? Furthermore, the limited attention Manipur received in the media has gradually diminished entirely. We remain unaware of the conditions within the refugee camps; we do not know if children are attending school or when they will be able to do so.

Arambai Tenggol and similar armed insurgent groups remain active, and the flames of ethnic violence continue to burn. In the hill areas, electricity has been absent for over a month, and in the refugee camps, three to four families are compelled to live in a single room. Aside from the lack of medical and other essential services, the drinking water is heavily polluted and rife with disease-causing organisms.

Barring a handful of news outlets, there is a significant lack of impartial news coverage available to the rest of the country. Conversely, neutral journalists have faced attacks and intimidation and have been driven out of their roles. It is evident that the long arm of the ruling BJP is behind these actions.

The history of ethnic conflict in the Northeast is indeed lengthy; however, it would be inaccurate to assert that there has been no sense of fraternity whatsoever. Undoubtedly, colonial rulers manipulated these conflicts into various political forms to serve their own interests. The involvement of the RSS and the Sangh Parivar—who were among the staunchest supporters of the British Crown—in this intricate landscape, as well as the resonance of Hindutva’s “victory” in the tribal-dominated areas of the Northeast, represents a history that is both complex and profoundly intriguing.

In the pre-colonial era, Manipur was a largely forested territory comprising both its plains and its hill regions, home to various tribes. It had a monarchy of its own distinct kind, with no formal land-revenue system. Each month, men were required to provide the king with ten days of unpaid labour. Skirmishes with Burma (present-day Myanmar) were a constant occurrence. From the late eighteenth century, Burmese aggression intensified, and large numbers of Manipuris (Meiteis from the valley) and Nagas were sent to Burma as captives and slaves.

This created an opening for the forceful entry of colonial power in the region. The Burma–British rivalry and Manipur’s strategic location paved the way for British control over Manipur. In 1762, a treaty of cooperation was signed with the king of Manipur. Manipur also aided the British army in suppressing rebel Naga and the Mizo groups from the Lushai Hills. It should be remembered that at the time, a large portion of Manipur’s labour force came from the Naga tribes. Later, during the Burma–British conflict, the then king sent Naga slaves to fight in the war on the British side. British officer James Johnstone wrote in his 1896 book My Experiences in Manipur and the Naga Hills that half the pay of these Naga soldiers went into the coffers of the king of Manipur.

Meanwhile, in 1845, the Kukis—driven from the Lushai Hills by other tribes (through colonial intervention)—came into the Naga Hills. Land seizures led to widespread violence and bloodshed, with many Nagas killed at their hands. The British attempt to create a buffer zone by settling Kuki villages between the Naga Hills and the Manipur valley sparked prolonged hostility, bloodshed, and countless deaths between the two tribes.

The colonial power put pressure on several leaders of independent-minded Naga sub-tribes, forcing them to sign agreements for security. The old relationship between Manipur’s rulers and the ruled began to change under colonial intervention, and inter-tribal rivalries began to acquire new political dimensions.

Even after the Treaty of Yandabo with Burma in 1826, the British, without consulting the king of Manipur, transferred the Kabaw Valley to Burma in exchange for a nominal annual compensation. Many Manipuris, primarily Meiteis, were subsequently relocated to Burma. Although a British agent took a seat in the royal court, Manipur maintained a degree of sovereignty until 1891. It is also important to note that during this period, the Meitei monarchy of Manipur assisted the British in quelling rebellions by other tribes in the Northeast.

In 1891, the Anglo-Manipuri War erupted due to succession disputes. Driven by anti-imperialist sentiments, Manipuri men and women fought valiantly to support their king. The British victory was ultimately inevitable, leading to Manipur becoming a subordinate princely state. It is also important to note that the British undermined all legitimate historical claims by the Kukis to their ancestral homeland. Different rulers, under both British rule and independent India, utilised them as fighting forces at various times, arming them according to the situational requirements. Written history has not always fully conveyed the complex, multifaceted nature of these events.

It was explained simply by the young owner of a homestay in the Imphal valley where I stayed. Although he was young, the owner possessed a deep understanding of his tribe’s oral history, which contrasted sharply with the rootless uncertainty experienced by many displaced urbanites.

Manipur as a Princely State under British Rule

From 1891 onward, the colonial government began to apply its policies of fostering ethnic antagonism with full force. Separate administrations were created for the Meitei-dominated valley and the Naga- and Kuki–Zo-dominated hill areas. In Manipur, as in the rest of the Northeast, the British adopted diverse and elaborate strategies to prevent political unity among tribal peoples.

The Meitei royal dynasty had its roots in the valley’s Meitei community. Naturally, the Meitei aristocracy were allies of the British. The Meitei upper class, already a Hindu elite with distinguished cultural standing and landholding privileges, grew even more influential under British patronage. In the eighteenth century, Hinduism entered Manipur, while the older religion, Sanamahism, remained strong. Through the long efforts of the RSS, it was gradually integrated into Hinduism, and now, under the patronage of the BJP, we have seen its renewed practice, the renovation of temples, and priests even receiving national awards.

There were also Muslims among the Meiteis, although they were, of course, not particularly influential.

Ethnic hatred intensified among the disadvantaged and conflict-scarred Naga and Kuki communities. In the hill areas, the British administration dispatched a significant number of Christian missionaries to convert the Nagas and Kukis en masse, which further deepened the religious and cultural divide with the Meiteis of the valley. Social interaction between the Meiteis and the Naga, Kuki, and Zomi communities was strictly prohibited and controlled.

In the period following the 1930s, the Nikhil Hindu Manipuri Mahasabha—later renamed the Nikhil Manipur Mahasabha—initiated broad-based movements for social and political reforms that did not include participation from the hill tribes. The Western-educated upper-class Meiteis largely benefited from these movements. In contrast, during the Kuki rebellion of 1917–1919—when the Kukis rose against the colonial rulers in protest of British aggression and the forced conscription of men into the army during the First World War—only a small fraction of Meiteis offered support on anti-imperialist grounds. The majority remained passive, while the aristocratic, pro-government segment of the Meiteis advocated for the suppression of the Kukis to preserve Meitei dominance.

To fully comprehend the intricacies of the Manipur conflict, one must recognise the colonial strategy aimed at exploiting the internal divisions among the fiercely independent, nature-protecting tribal communities of the Northeast for the purpose of seizing forest and mineral resources and consolidating power.

After the transfer of power in 1947, the aspirations for autonomy in these regions were crushed through militarisation (as is widely known, due to AFSPA), repression, the creation of smaller “internal colonies”, and the wholesale disregard for the long-standing traditions of self-governance among local indigenous peoples, as they were forcibly integrated into the Indian Union.

Therefore, far from empowering ordinary communities, Article 371 has frequently co-opted elites while deepening the sense of alienation on the ground. The irony is stark: a clause framed to protect the margins has ended up protecting those at the top. For many in the Northeast, the real story of Article 371 is not cultural autonomy but political co-optation—an arrangement that secures Delhi’s control by compromising local democracy.

The Sangh Parivar’s centre stage

From the 1960s on, the RSS began planning the expansion of aggressive Hindu nationalism from Assam to Arunachal Pradesh, aimed at erasing the Northeast’s religious and cultural diversity. The 1966 Assam Conference in Assam, organised under the banner of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, generated significant enthusiasm. Golwalkar himself attended and stayed for three days. Through the RSS’s dedicated efforts, several leaders of different tribal groups were brought to the conference — among them, the most important figure was the popular anti-British Naga leader, Rani Gaidinliu.

Leader of the Heraka movement, Gaidinliu had fought to protect Naga culture and identity against Western influence and Christian conversion. Although she was close to the Congress, the party placed no obstacles in the way of the Sangh Parivar’s activities. The Congress believed such RSS initiatives would aid its own goal of national integration.

In any case, the renovation of the Parasuram temple in Arunachal marked the beginning of the plan’s implementation. By targeting the otherization of Christians and Muslims, the scheme gained success. In Manipur, the Muslim Meiteis have no particular social influence, but their presence has served the purposes of the RSS. Across the region, countless residential schools were established for underprivileged vanvasi (forest-dwelling) and girivasi (hill-dwelling) children. These schools, like other RSS-run institutions, taught Sanskrit and the ideology of creating a Hindu Rashtra — everything except the child’s own culture. The only difference was that alongside Savarkar’s portrait, Ambedkar’s was also hung here. For years, photographs of Rani Gaidinliu and other tribal leaders were used as those of religious–spiritual gurus so that in the children’s consciousness, their culture and religion would be internalised as Hinduism.

Pictures of Goddess Lakshmi, labelled as Bharat Mata, adorned the walls of these schools. Sanskrit mantras were displayed for the children to recite, even though they did not comprehend their meaning. Large letters on the wall proclaimed, “Knowledge leads to unity; ignorance leads to diversity.”

The Congress thought it was gaining much—so it indirectly fanned the flames of this aggressive Hindutva politics. Those segments of the tribal population that Congress elites could not win over are now, in significant numbers, enabling those very upper-caste elites to maintain power.

Today, the Janjati Vikas Samiti and the RSS, part of the broader Sangh Parivar, have achieved success. With the exception of Mizoram, the entire Northeast is now under BJP control. Divisive and violent otherization campaigns, coupled with an imposing Hindutva, are permeating the very fabric of the region. One of the responses to this pervasive assault is Manipur.

Current Unrest: Ongoing Violence

The unrest that has persisted since May 2023 is widely understood to have a clear cause. Tensions began over a Manipur High Court order to include the Meitei community in the Scheduled Tribes list. In this context, let us quote the following excerpt from an IWGIA report:

“In 1948, a merger agreement between Manipur State and the National Government of India was made. This agreement only covered the valley area, also known in pre-colonial times as the Princely State under which the Meitei were ruled. Historically and traditionally, the Meitei occupied the valley lands of the region while the Nagas and Kukis are hill people and have always wanted to remain independent. However, adding a level of complexity that continues to exist today, the Meitei claim that the entire territory of the region, including the hills, is the traditional territory of Manipur, whereas it is in fact only the valley—out of fear that this would bifurcate the administration of the areas, allowing separate political entities to remain in control of both the hill people and the Meiteis’ land in the valley.

These issues remain unresolved, and the current conflict is directly related to that.

The Nagas have found it difficult to get involved in the current conflict because the Kuki raised the issue of separate administration, which by default involves administration and ownership of land. However, the Nagas are providing relief to Kuki victims as they are in agreement that the Meiteis should not receive Scheduled Tribe status and upend the delicate political balance in the area and lose the independence they have been fighting for centuries.”

The apparent pretext is really a problem that has been deliberately provoked.

Since the Naga-Kuki-Meitei triangular conflict, the ruling BJP has sought to extract various political benefits by supplying money and weapons to different insurgent groups; according to official figures, 5,600 weapons and 650,000 rounds of ammunition have gone missing from state armouries. The reasons for dragging the people of Manipur into this self-destructive frenzy are no mystery either.

Drug Trade

The poorest farmers cultivate poppy after receiving financial advances from drug mafias for fertilisers and pesticides. Since India has licensed poppy cultivation, the drug trade has shifted from Myanmar to Manipur. Although people from all three major communities in the state—the Kukis, Nagas, and Meiteis—are involved in illegal poppy cultivation for drug production, control of the trade naturally rests largely in the hands of the Meiteis, as they are the more affluent group. By spreading the narrative that only the Kukis are the criminals engaged in illegal cultivation, former Manipur Chief Minister Biren Singh sought to bring the entire racket under his control. Critics claim that his personal investments in this trade are not insignificant. In doing so, he managed to successfully attach a Hindu–Christian angle to the old ethnic rivalry.

According to local civil activists, the annual revenue from the drug trade in Manipur is estimated at ₹50,000 crore (approximately €5.5 billion), nearly double the state’s annual budget of ₹30,000 crore (about €3.3 billion). Such a vast network cannot function without political backing—especially from those in power. Former Assistant Superintendent of Police Thounaojam Brinda stated plainly in an interview, “The Chief Minister of Manipur (Biren Singh) is not fighting against the illegal drug trade; rather, he is part of it—acting as a patron and protector of the drug mafias.” She has faced immense pressure for showing such courage and has possibly resigned from her post.

State and Corporate: The Neoliberal Joint Venture

Across India, forest-dwelling Adivasi communities are being uprooted, brutalised, raped, and massacred so that forests and mineral wealth can be seized. Manipur’s hills and forests are no less rich in natural resources—so why would they be spared?

So far, constitutional safeguards have kept the hill regions under the control of the hill tribes, slowing corporate penetration. But granting Scheduled Tribe status to the Meitei community would inevitably unsettle both the Kukis and the Nagas—this should be obvious to anyone. Once the Meiteis secure land rights in the hills, it is evident that corporations will collaborate with them, displacing people under the guise of “development”. Even a child can see where this leads.

The BJP’s support base in Manipur is overwhelmingly Meitei—and laced with Hindutva. Inciting communal violence to achieve its goals is the BJP’s oldest, and perhaps only, political craft. In Manipur, they’re playing the same script again.

Manipur’s Ordinary Voices: Pain Without Hatred

When I went to Imphal last December, I had to get an Inner Line Permit to enter the Manipur valley and the Naga hill districts. The Kuki hill areas were, of course, off-limits. Even after I returned to Kolkata, an official from the department called to check whether I had indeed left Manipur.

Still, in my very limited travels, one thing struck me: the unpoisoned hearts of ordinary Meitei people. In Meitram, a small rural area just 2 km from Imphal airport, I stayed in a homestay run by a young couple. Their business has nearly collapsed—there are no tourists. The young woman is cheerful by nature, but a trace of sadness seeps out once you talk to her for a while. And it’s not simply about the downturn in business.

“Didi, tell me, why is this happening? We were living so well. Will we never be able to go to the hills again? Will things never go back to how they were?” Her eyes well up with tears.

Faced with such questions, there’s nothing to do but fall silent.

Even if outsiders can visit, Meiteis themselves are not safe in Naga hills. Yet I did not hear a single curse against Kukis from her lips. Her only, fragile question was whether everything would ever be all right again.

Her husband drove me to a few places, and we spoke a lot along the way. I tried asking in roundabout ways, but found no bitterness in his words. He had studied outside Manipur before returning home to run the homestay. They live in a joint family; his father is a retired government employee. When I learn that his younger brother is a fine arts graduate from Visva-Bharati University, I am moved. He tells me—

“I don’t blame the Kukis. They never really had a place of their own. Everyone used them as hired musclemen. Only in the last generation or two had they begun to study—and now they’ve been handed guns.”

Instead, he is bewildered and exhausted by the muscle-flexing of self-styled “protector” groups like Arambai Tenggol. Ordinary people are being bled dry with constant demands for “contributions.” They had never seen such groups before. He doesn’t say much about where they come from or how they’re funded—but he doesn’t deny the role of government patronage either.

There’s a tense stillness hanging over Imphal. One morning, I set out to see Loktak Lake — these days, hardly anyone goes there. I spoke on the phone with a hotel owner named Shiljendra. He told me bluntly: “You’ll have to come, look around, and leave. I’ve had to shut down the hotel. It’s on the Kuki–Meitei border zone. I can’t take responsibility for anyone’s safety.”

I set out early and arrived at Loktak. Shiljendra turned out to be a very young Meitei man. He had studied “rural development” and, with assistance from local residents, had built an eco-stay — a beautiful place. But now, it’s closed.

He made coffee, and we sat chatting. Calmly, he laid out the situation, with no trace of anti-Kuki sentiment. As the conversation progressed, we both realised we leaned to the left. Before I left, he said, “Come again once this trouble is over. This time you couldn’t stay.” Then he added, “I’d once been to Kolkata. You have that big market for books, don’t you…?”

I prompted him: “Yes, College Street…”

He smiled: “I went there… bought some volumes of Marx and Engels.”

With that bright, open smile, he shook my hand. In moments like these, it’s difficult to articulate one’s feelings. I carried that smiling young face back with me, etched in my heart.

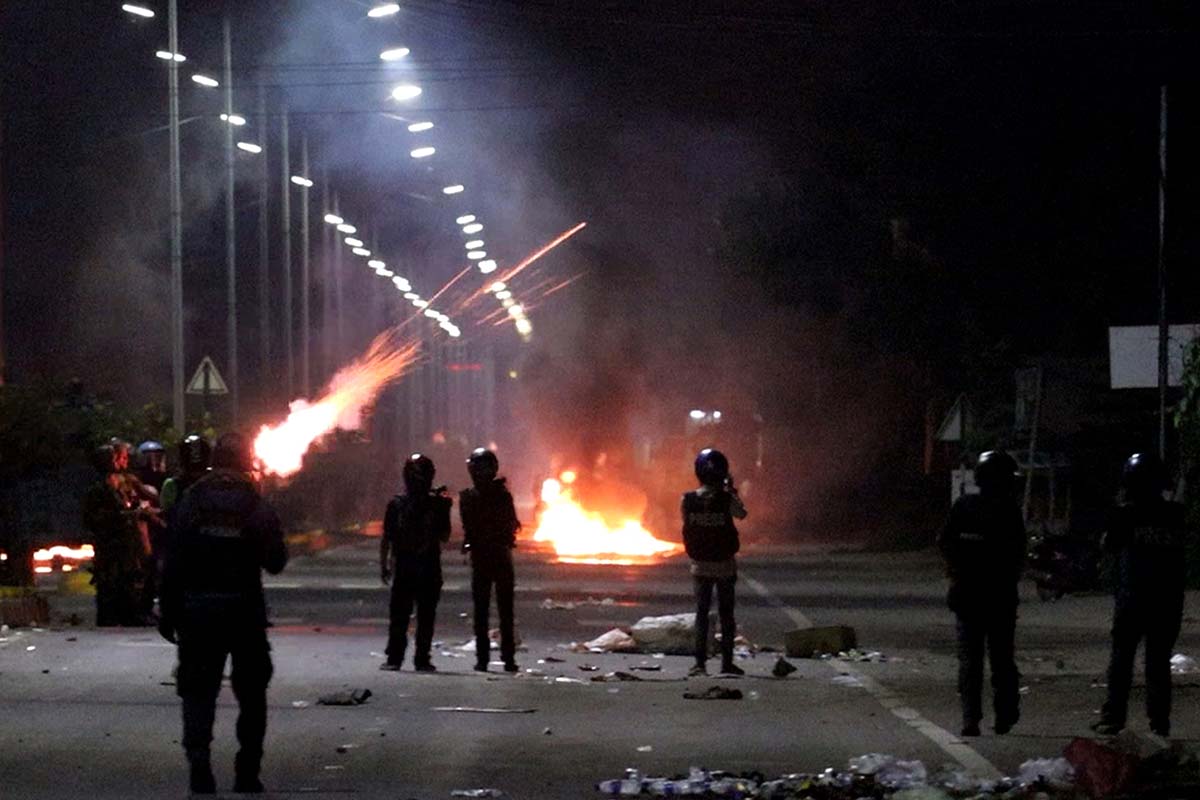

I went to Ukhrul, a Naga hill district, for two days. The day I boarded the bus out of Imphal, bombs exploded, shots were fired, and a bandh (general strike) was called. On the way, I encountered military checkpoints. In some areas, the road passed the entrances to Kuki regions. There, alongside the army, young Kuki men stood armed, manning their own checkpoints. They didn’t even glance at outsiders. The same was true for Meitei zones.

A quiet unease crept in. Would there be a curfew in Imphal? Would the internet still be functioning? Would I make it back to Imphal in time? Would I even catch my flight home?

When I reached Ukhrul, it felt like a different Manipur altogether — Christmas carols in churches, sports tournaments for children in every field. Each church, or the other, organised an event. I spoke to a few of their leaders. Some lived abroad, returning only at this time of year. They ran charity drives. Many of them, I discovered, were ardent supporters of Modi.

I let these contradictions wash over me. After all, everyone treated a guest with warmth and care.

Ima Keithel and the Power of Meitei Women

In Manipur, men were historically required to work ten days each month as forced labour under the king, along with their other responsibilities. Consequently, the establishment and management of joint markets by Meitei women is a notable achievement with deep historical roots. Presently, the women-run market in Imphal, known as Ima Keithel, has gained international recognition for its distinctive management system. Dr. Haobam Bilashini Devi explores the history of Ima Keithel in her book, Images: Impact on Memory:

“Woman Market is an institution in its own right with specific do’s and don’ts… Any plot or vendor allotted to a woman could or could not be inherited by her son or daughter or daughter-in-law. Under no circumstances can it be sold away or disposed of… Nor is it governed by the land revenue department… It is an institution of Manipuri women.”

It is nearly impossible to articulate the remarkable self-possessed autonomy of Meitei women across all social strata, who navigate modernity in a manner that is both grounded and unpretentious. When gruesome videos depicting the abuse of Kuki women circulated on social media, I found myself heartbroken, pondering the whereabouts of the Meitei mothers of those naked processions. I then witnessed Sharmila Chanu’s impassioned response—her protest and her incisive critiques of both the central and state governments. Upon my arrival in Manipur, I observed that the voices of ordinary Meitei women echoed Chanu’s sentiments: unequivocal, fearless, and denouncing the atrocities. In my brief conversations with them, I noted that they did not assign blame to Kuki women for the abuse. However, despite their organised marches and protest gatherings against the oppression of Kuki women, their resolve and solidarity appeared elusive from a distance.

Bilashini Devi’s praise is far from exaggerated. About Ima Keithel, she writes:

“It is the centre of all decision-making. All women’s movements in recent past have had their origins in this marketplace. From time to time, women decide major actions to take up against atrocities, injustice, oppressive laws, violence and so on.”

It is not only the large central Ima Keithel in Imphal that conveys this formidable power; the rural, local Ima markets also provide a glimpse into it. However, beyond the market, across the Elephant Bridge, the theatres stand closed. These stages, once vibrant with the extraordinary theatrical and dance performances of Manipur’s powerful women, are now silent. Due to the language barrier, I struggled to understand much and found it difficult to express myself fully. Yet, who is to stop me from imagining? Not everyone speaks Hindi or English, and my proficiency is limited to both these languages beyond my mother tongue.

Observing the city’s energetic, capable, and industrious young women engaged in every conceivable sphere, I was filled with wonder. Greeshma Kuthar’s podcast informed me about how Kuki women established their own human rights organisations. Their guiding principle is Jangna-Dap, which translates to ‘solidarity’. For those who have lost everything due to violence, they mobilise support from Kuki communities across India and abroad, working tirelessly to assist refugees and maintain hope.

The Current State of Manipur

Children are bearing the heaviest burden. Many have been out of school for months, their education and childhood suspended. Even more precarious are the children of inter-community marriages. Kuki-Meitei or Meitei-Kuki couples are forced apart, each confined to their own areas or segregated refugee camps. No one knows when—or if—they will be reunited. If reunions happen, they would have to take place outside the state, a near-impossible prospect. Meanwhile, children living with their mothers are often denied contact with their fathers, growing up in fractured families amid fear and uncertainty.

The condition of the Kukis is indescribable. During that time, Kukis living in the valley could not even bury the bodies of their relatives. The air in the camps is heavy with the cries of orphaned children.

Even after President’s Rule was imposed, weapons continue to flow into the region from Myanmar through the hill borders of five districts. The violence continues unabated. In the border village of Moreh, the Kukis drove out Meitei traders after killing some of them. What was once a bustling marketplace is now dead. Has anyone been able to return to their homes? The local administration has claimed that 10,000 refugees have yet to return home and that they will be able to close the camps by December of this year. This report is from July 5, 2025.

However, what is the actual situation? I heard on a news podcast just last month that the displaced people are spending their days in severe economic hardship and humiliation. There has been no resolution in terms of government aid or rehabilitation. People are waiting—for elections and for an elected government.

[This article was originally published in bengali in 4 No. Platform Webzine on 25th July 2025]

Photo credit : Ima Keithel – By Goumisao – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40953365

Editorial Board Member of Alternative Viewpoint

Equilibrado de piezas

El equilibrado representa una fase clave en las tareas de mantenimiento de maquinaria agricola, asi como en la produccion de ejes, volantes, rotores y armaduras de motores electricos. El desequilibrio genera vibraciones que incrementan el desgaste de los rodamientos, provocan sobrecalentamiento e incluso pueden causar la rotura de los componentes. Para evitar fallos mecanicos, resulta esencial detectar y corregir el desequilibrio a tiempo utilizando metodos modernos de diagnostico.

Metodos principales de equilibrado

Hay diferentes tecnicas para corregir el desequilibrio, dependiendo del tipo de pieza y la intensidad de las vibraciones:

Equilibrado dinamico – Se aplica en elementos rotativos (rotores y ejes) y se realiza en maquinas equilibradoras especializadas.

Equilibrado estatico – Se usa en volantes, ruedas y otras piezas donde es suficiente compensar el peso en un unico plano.

La correccion del desequilibrio – Se realiza mediante:

Taladrado (retirada de material en la zona de mayor peso),

Colocacion de contrapesos (en ruedas y aros de volantes),

Ajuste de masas de balanceo (por ejemplo, en ciguenales).

Diagnostico del desequilibrio: equipos utilizados

Para identificar con precision las vibraciones y el desequilibrio, se emplean:

Maquinas equilibradoras – Miden el nivel de vibracion y determinan con exactitud los puntos de correccion.

Analizadores de vibraciones – Registran el espectro de oscilaciones, detectando no solo el desequilibrio, sino tambien otros defectos (por ejemplo, el desgaste de rodamientos).

Sistemas laser – Se emplean para mediciones de alta precision en componentes criticos.

Especial atencion merecen las velocidades criticas de rotacion – condiciones en las que la vibracion se incrementa de forma significativa debido a fenomenos de resonancia. Un equilibrado adecuado evita danos en el equipo bajo estas condiciones.