“The ruling powers of capitalist society who held the fate of the nations in their hands, the monarchic as well as the republican governments, the secret diplomacy, the mighty business organizations, the bourgeois parties, the capitalist press, the Church – all these bear the full weight of responsibility for this war which arose out of the social order fostering them and protected by them, and which is being waged for their interests.”

Manifesto, International Socialist Conference at Zimmerwald, 1915.

Amidst the growing enthusiasm for militarisation and the escalating imperialist crisis, the call for clarity emerges as both a clarion call and a revolutionary imperative. The Marxist understanding of war, forged through the tumultuous history of the twentieth century, serves as a valuable resource for navigating the perilous path of the current era. This theory goes beyond the basic ideas of “national security” versus “external aggression,” “East” versus “West,” or “democracy” versus “autocracy,” and instead uses a scientific method to understand class struggles and a materialist view of history.

Additionally, it is crucial to explore these issues in depth, as the questionable role of the so-called “left” forces on either side of the Indo-Pakistan border in recent times has raised significant questions and undermined progressive positions within the subcontinent.

The nationalist positions expressed by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the Communist Party of India, and certain sections of the Pakistani left represent a significant deviation from the Leninist understanding of war. Their perspectives reflect a re-enactment of the 1914 collapse of the Second International, during which socialist parties abandoned proletarian internationalism in favour of nationalism. Lenin and Trotsky characterised this betrayal as “social patriotism“, a tendency that ultimately contributed to the defeat of the German Revolution, the murders of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, the isolation of revolutionary socialists, and the perpetuation of international conflict. In contemporary contexts, these patterns are increasingly evident: the Indian Left legitimises Modi’s aggressive actions as “defensive,” while segments of the Pakistani Left justify their army’s actions as a form of anti-Hindutva “resistance”. Both groups appear oblivious to the inherent class nature of their respective states, failing to recognise that patriotism founded on nationalistic falsehoods is not true socialism; rather, it is reformist careerism disguised in leftist rhetoric. This decline is not limited to South Asia but is part of a broader trend within the global system.

Also, the rise of “multipolar” imperialist and sub-imperialist blocs does not contribute to the establishment of peace; instead, it is resulting in heightened warmongering and militarisation. The emergence of far-right factions, as illustrated by Trump and his affiliates, in conjunction with the Zionist-fascist coalition endorsing Israel’s manoeuvres in Gaza, encapsulates this phenomenon. J.D. Vance’s sworn affidavit, asserting that the Indo-Pak War is “none of our business,” illustrates not a stance of isolationism but rather a calculated indifference that allows for violence while upholding imperialist control via proxy conflicts. The global landscape is witnessing a troubling desensitisation to the stark truths of warfare, as the Russian offensives in Ukraine and Israel’s methodical aggression towards Palestinians lead to the erasure of nations with minimal repercussions. The international framework of law, previously a disingenuous instrument employed by the elite, now finds itself in a state of disarray. In this framework, India’s belligerent position—illustrated by violations of the Indus Waters Treaty and heightened defence procurements—ought to be regarded not as mere provocations but as a regional reflection of the broader phenomenon of global warmongering and militarisation.

Against this backdrop, the crisis of Western capitalism, combined with the rise of Chinese hegemony, introduces a new layer of complexity. A noticeable shift in the foundations of imperial alignments can be observed, influenced by the emergence of high-tech warfare and the economic destabilisation facilitated by junior states such as India and Pakistan. The primary concern is not about aligning with either of the imperial blocs but rather about fostering a non-aligned proletarian internationalism that actively resists becoming a mere tool of war for either side.

This piece reaffirms the Marxist position against all forms of imperialism, including the war and false patriotism that often accompany it. We advocate for a class war against all warmongers. The true enemy lies within.

Opposition to War, Militarism and Capitalist Patriotism

Marxism analyses war through a critical lens, employing historical materialism. In contrast to bourgeois ideologies, which often emphasise ideals or morals, Marxism refrains from making definitive statements for or against war. There is neither an outright condemnation nor unqualified praise for violence. Instead, Marxists advocate for a thorough examination of each war, considering its specific historical context, class divisions, political interests, and potential repercussions for workers globally. For Lenin, “from the point of view of Marxism (…) the main issue in any discussion by socialists on how to assess the war and what attitude to adopt towards it is this: what is the war being waged for, and what classes staged and directed it” (Lenin, War and Revolution, 1917). It is important to differentiate between critiquing the method of warfare and assessing the desirability of the war itself.

The Marxist understanding of war is both general and particular. It firmly rejects the liberal and moralistic perspective, which views war merely as a result of ‘bad politics’ or the actions of irrational leaders; instead, it attributes the cause of war to the very nature of capitalist society. War should not be considered an aberration of capitalism; rather, it is one of its most violent manifestations. As Lenin articulated with precision, “War is the continuation of politics by other means.” He quoted Clausewitz while also incorporating a class dimension: it is bourgeois politics conducted through the instrument of military force.

Marxism does not glorify either peace or war. It does not categorise all wars as good or bad; instead, it analyses each conflict based on its class character, the forces involved, and its historical context. Marxists initiate their analysis by posing the following questions: who benefits, who suffers, and how does the class struggle evolve as a result of war?

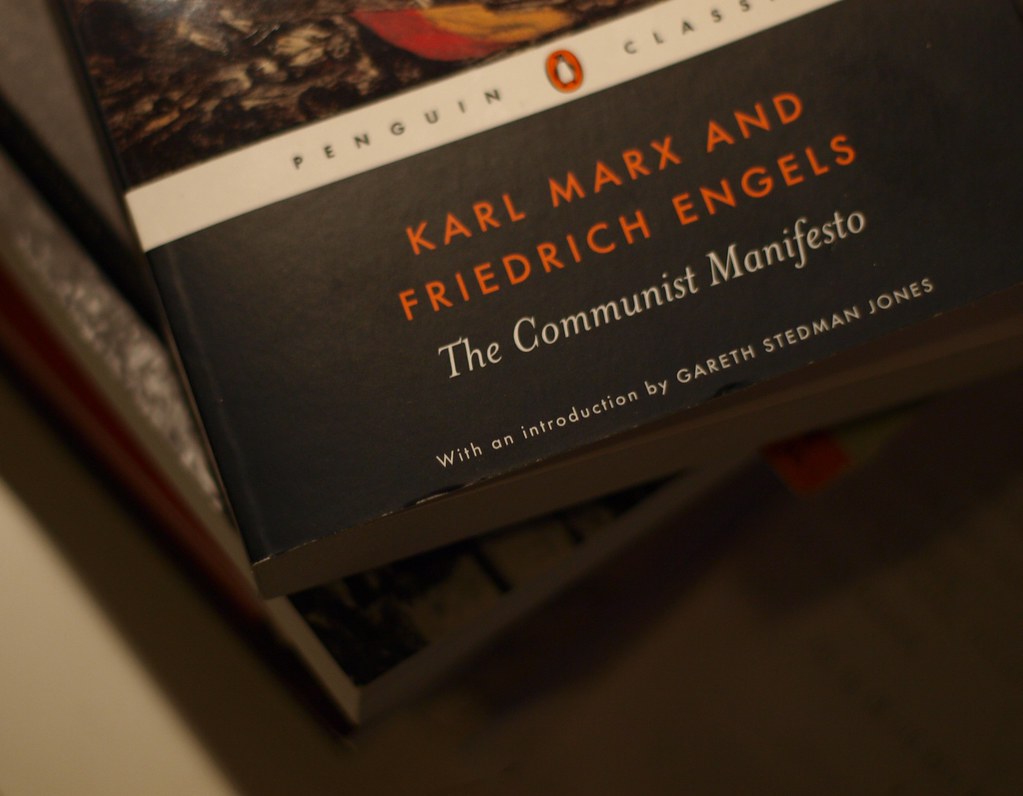

The capitalist class exploits notions of patriotism and national unity during wartime, yet this is not genuine. As Marx states in the Manifesto, “The working men have no country.” The statement does not imply a complete rejection of nationalism but rather critiques the notion that the working class must sacrifice its own interests for the state’s benefit. War often serves as a tool for the ruling class to divert the populace’s attention from domestic issues—such as economic crises, worker discontent, or political instability—towards an external adversary. In every instance of imperialist war, the working class suffers the most, while arms manufacturers and capitalists reap the rewards.

Photo Credit – Openverse

Lenin’s analysis of World War I remains a crucial interpretation of the conflict. He condemned the betrayal of the Second International, whose leaders, under the guise of ‘defending the Fatherland,’ voted in favour of war appropriations and aligned themselves with the bourgeoisie. Lenin characterised these actions as social chauvinism—publicly advocating socialism while succumbing to nationalist impulses. The war is a predatory imperialist war,” Lenin asserted in April Theses ( The Tasks of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution, 1917). “Social-chauvinism, being actually defence of the (…) imperialist bourgeoisie, is the utter betrayal of all socialist convictions.” (Socialism and War, 1915)

The Marxist perspective adopted the notion of revolutionary defeatism, suggesting that the ruling classes’ loss in an imperialist war might not be detrimental to the working class. Lenin urged the working class to transform the imperialist war into a civil war and to fight for their class by harnessing their national sentiments. This approach proved effective during the October Revolution, as the Russian working class, led by the Bolsheviks, successfully overthrew their imperialist government and withdrew from the war.

We must differentiate this clear-headedness from the petty-bourgeois left, which tends to shift its position. Some contend that all wars are inherently evil, failing to distinguish between imperialist wars and wars of national liberation. Others support one form of imperialism over another, effectively taking sides in international politics. Marxism does not align with either of these perspectives. It does not automatically declare that all wars are evil; instead, it evaluates each situation within the framework of class struggle. The Vietnamese resistance against U.S. imperialism and the national liberation movements in Africa and Latin America—these were not simply conflicts between empires but just wars waged by oppressed peoples.

Meanwhile, Marxists do not regard war as necessary. Even just wars cause suffering, devastation, and alterations in the way people perceive politics. War requires militarism, chains the working class, and tends to bring more power to the government. Due to this, Marxists regard war as a strategic scenario: not as an end but as a site for conflict, chaos, and the possibility of significant changes.

Lastly, the Marxist stance against war parallels its opposition to capitalism. As long as capitalism persists, imperialist rivalry, colonial exploitation, and expansionist wars will continue. Only by reorganising society towards socialism, which abolishes the need for profit and national rivalries, can we break the cycle of war.

Marxists must be prepared to engage in conflict—not to justify war, but to fight for peace by dismantling its causes. Peace transcends mere rhetoric; it represents a manifesto for workers’ empowerment and world revolution.

Imperialism

With the onset of the twentieth century, the dominance of monopolies, trusts, and financial capital signalled the beginning of a new era in world capitalism, referred to as ‘imperialism’, which concurrently gave rise to a new form of conflict: imperialist wars. The twentieth century became irrevocably linked with these wars. By the end of the nineteenth century, capitalism had surpassed the limitations of national economies, evolving into a global competition for markets, essential raw materials, inexpensive labour, investment opportunities, and territorial annexations. This new phase of capitalism—imperialism—has served as the principal driving force of the system since that time. The most significant distinction between classical imperialism and contemporary globalism is the shift from territorial colonies to neocolonial institutions, which now serve as the primary instruments of economic domination.

The international economy, built on competing national capitals, suffers from a lack of a central cohesion to guide economic, monetary, or fiscal policy, leading to periodic instability. This absence of coherence means that there is no mechanism to prevent or limit the actions of certain segments of the capitalist class. As competitive pressures among national capitals create a cycle of global economic disruptions, each nation depends on its state power for military and diplomatic support in this anarchic international competition. Consequently, this process has resulted in a century characterised by continuous warfare and widespread devastation, with not a single year of the last century free from conflict.

New imperialist wars brutally reveal the reactionary nature of contemporary capitalism and its increasing necessity for socialist transformation. The vast riches reaped from imperialist undertakings and the progress of humankind in science and technology have been less often used for human welfare or nature. Instead, it has led to the manufacture of lethal weapons of mass destruction. Recently, as a mouthpiece of the financial oligarchy, the Wall Street Journal highlighted such a system’s absurd priorities in its editorial commentary on the war against Serbia: “We’d rather see the money go to buy bombs that might save lives than be used to expand the welfare state.”

The bombs—labelled as ‘life-saving’ instruments of capitalism—illustrate the regressive characteristics inherent in imperialist war: a chilling escalation of mass killing (with 25 million dead in World War I and 55 million in World War II) alongside a transformation of the object of violence from military personnel to civilians. In the lead-up to the outbreak of the World War I, civilian casualties typically represented 10 per cent of all casualties. However, in the World Wars and the Vietnam War, civilians constituted the vast majority of those killed. In NATO’s war against Serbia, it is estimated that 80-90 per cent of those killed were civilians, primarily of Serbian and Albanian nationality—termed ‘collateral damage’ in capitalist jargon. These grim statistics serve as some of the strongest condemnations of a system in which, far from being progressive, we witness a modern form of barbarism. Lenin contended that imperialist wars are not wars for progress in human development but rather predatory conflicts between contemporary marauders vying for spoils. The ruling elites compete to acquire resources and establish the exploitation of others. Neither side in a predatory war is engaged in genuine historical progress or working for the benefit of the working class—no ‘lesser evil’ can be supported.

Imperialists justify their actions by claiming they are merely seeking their rightful portion. The Nazis, for instance, rationalised their expansionist ambitions as a necessity for living space denied to Germany, which they regarded as a ‘have-not’ country under the ‘plutocratic’ powers led by Britain. Similarly, Mussolini’s Italy considered itself a ‘proletarian nation’—less affluent than the major imperial nations, which it condemned as bourgeois.

No matter whether they are small-time or big-time culprits, established imperialist powers or newly emerging ones, aggressive or maintaining the status quo in policy, the outcome remains the same: we condemn them all. We are opposed to all imperialist wars, recognising them for what they truly are: reactionary battles for conquest and dominance. These wars serve only the ruling class, who seek to expand their wealth, power, and privileges through the domination of not only their domestic working class but also that of foreign peoples. The defenders of one side in these imperialist wars often go to great lengths to justify their opponent’s imperialist actions—such as exploitation, annexation, and other aggressions—while conveniently overlooking the transgressions of their ruling class, whose imperialism is frequently disguised as democratic, anti-fascist, or justified by some other noble-sounding rationale. In the early history of capitalism, the ruling class was able to align its goals with national objectives. However, with the advent of imperialism, it becomes increasingly difficult for people to accept that the aims of capitalism are synonymous with national goals. The imperialist forces masks their ulterior motive, i.e., seeking greater profits, exercising capitalist hegemony or acquiring resources. Instead, the ideological instruments of capitalism—such as media, churches, and universities—endeavour to persuade the masses that the wars they are urged to fight are noble causes: intended to prevent genocide, uphold democracy, defend against hostility, and promote other ideals, all while obscuring the true motives of imperialism and the interests of the capitalist class. For socialist opposition, the primary task is often to dismantle such ideological illusions, thereby revealing the authentic goals and political realities underpinning these wars.

Individual Wars: From Prussia to Vietnam

A revolutionary socialist analysis demands that every war is examined in its particular historical situation. This approach circumvents the risks of abstraction and moralism and grounds analysis in political conditions and class forces. Now we’ll look at a sequence of great wars that reflect the gigantic complexity and contradiction of war throughout capitalist history.

1. The Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871): A War That Changed Character

In Marxist analysis, the Franco-Prussian War serves as an example of a conflict whose class dynamics evolved throughout its course, necessitating adjustments to revolutionary strategy. Marx and Engels, in their examination of the war, underscored the importance of a specific historical analysis, rejecting any abstract or timeless category of warfare.

When the war commenced, Marx and Engels did not entirely denounce it. They viewed it as a defensive struggle between a half-feudal Prussian state and the expansionist ambitions of the French Second Empire under Napoleon III. In a letter dated July 20, 1870, to Engels, Marx stated, “The French need a thrashing. If the Prussians win, the centralisation of the state power will be useful for the centralisation of the German working class.”

Although they were not entirely satisfied, Marx and Engels welcomed the unification of Germany and regarded it as a significant historical development. They believed that the unification of Germany under Prussia would halt the gradual decline and fragmentation of German states, stimulate capitalist growth, and create favourable conditions for a modern workers’ movement. Engels elaborated on this notion in a letter to Marx dated 15 August 1870: “If Germany wins, French Bonapartism will at any rate be smashed, the endless row about the establishment of German unity will at last be got rid of, the German workers will be able to organise themselves on a national scale…”

Photocredit – Openverse

However, Marx later noted that this viewpoint was evolving and did not necessarily support Bismarck’s aggressive policy. When the Prussian army invaded France, surrounded Paris, and sought to annex Alsace and Lorraine, Marx condemned the war for transforming into an imperialistic and avaricious campaign. Marx declared in his initial address to the General Council of the International Working Men’s Association on 23 July 1870 said, “On the German side, the war is a war of defence” (…) If the German working class allow the present war to lose its strictly defensive character and to degenerate into a war against the French people, victory or defeat will prove alike disastrous.”

Bismarck had intended to occupy French territories, and on the 9th of September 1870, the First International released a Second Address, wherein it said: ““We,” they say, “we protest against the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine. And we are conscious of speaking in the name of the German working-class. In the common interest of France and Germany, in the interest of peace and liberty, in the interest of Western civilisation against Eastern barbarism, the German workmen will not patiently tolerate the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine …. We shall faithfully stand by our fellow-workmen in all countries for the common International cause of the Proletariat!”.”

Marx distinguished between a war of national defence, which he initially supported, and a war of conquest, which he condemned. He warned that the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine would provoke future conflicts and harm Franco-German relations. His prediction proved accurate: the annexation ignited deep resentment in France fuelling French nationalism.

In addition, Marx observed that Bismarck’s wars were not aimed at liberating the German people but rather at consolidating the power of the Junker aristocracy and the Prussian monarchy. It was also an attempt to lay the foundations of a capitalist Germany. The significance of class leadership remains evident, even within the context of liberal wars. It is important to note that Marx’s support for German unification should not be construed as an endorsement of Bismarck’s despotism; rather, it reflects a recognition of the historical necessity for capitalist development, which would facilitate the further development of class contradictions.

The Franco-Prussian War serves as a reminder for Marxists: we can observe not only who instigated the war but also its historical purposes, the politicians responsible for it, and the evolving political climate. We cannot endorse a war—regardless of its supposedly virtuous justifications, such as national unity or protection—without satisfying a precondition.

After the war, Marx and Engels observed the emergence of the Paris Commune in 1871, which marked the initial instance of the dictatorship of the proletariat. This development underscored the distinction between the proletarian revolution and the Bonapartist government it opposed, as well as the Bismarckian state that sought to suppress it. It served as definitive evidence that their struggle against the reactionary forces unleashed by the war was inextricably linked to a broader revolutionary movement.

2. World War I (1914–1918): The Imperialist Slaughterhouse

World War I significantly altered the course of Marxist understandings. It resulted in the dissolution of the Second International and underscored the shortcomings of social-democratic nationalism. The principal socialist parties in Europe supported the war effort and aligned themselves with their respective bourgeois classes, forsaking internationalism in favour of patriotic sentiment. In his work Socialism and War (1915), Lenin remarked, “This is a war firstly, to fortify the enslavement of the colonies by means of a “fairer” distribution and subsequent more “concerted exploitation of them”; secondly, to fortify the oppression of other nations within the “great” powers, for both Austria and Russia (Russia more and much worse than Austria) maintain their rule only by such oppression, intensifying it by means of war; and thirdly, to fortify and prolong wage slavery, for the proletariat is split up and suppressed, while the capitalists gain, making fortunes out of the war, aggravating national prejudices and intensifying reaction, which has raised its head in all countries. even in the freest and most republican.”

World War I did not herald progress. It was neither a war of national freedom nor a democratic endeavour. Instead, it was a conflict between empires—France, Britain, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia—vying for colonies, markets, and dominance. Lenin referred to it as a war to “redivide the world”. The Bolsheviks opposed the war and adopted a stance of revolutionary defeatism, hoping that their ruling faction would be defeated, thereby allowing them to transform the situation into a civil war.

Karl Liebknecht cast a solitary no vote against war funds in the Reichstag. Following his lead, Rosa Luxemburg wrote in The Junius Pamphlet, “The triumph of imperialism leads to the annihilation of civilization (…) Today, we face the choice exactly as Friedrich Engels foresaw it a generation ago: either the triumph of imperialism and the collapse of all civilization (…) or the victory of socialism.”

3. World War II (1939–1945): Imperialist Rivalry to Anti-Fascist Struggle

World War II differed from World War I. It began as a conflict between powerful nations, but the emergence of fascism altered its political character significantly. According to Trotsky in his 1932 essay, What Next?, fascism was not merely a straightforward reaction; rather, it was a serious indication of the ills of capitalism, and its accomplishment was a massive threat to the proletariat.

The Soviet Union’s entry into the conflict marked a turning point. They had initially compromised with Germany with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 with immediate impact on the Polish working class; but in 1941, the USSR was up against Nazi Germany. The war transformed significantly: the Eastern Front became a battle for survival, not only for the Soviet nation but for the working class of the world. The Nazi regime’s aims were not merely to acquire land; they wanted to eliminate communists, Jews, Slavs, and anyone else who was against their total domination.

For the proletariat, the war against Nazi Germany was a defensive, just, and anti-fascist war. Even after the capitulation of the Stalinist bureaucracy, the Soviet defence of Stalingrad and the eventual liberation of Eastern Europe demonstrated that fascism could be defeated only through armed struggle, not peaceful appeals.

There were also some reactionary dimensions in the war. Although the Soviet Union and the United States, as well as British imperialism, worked together, they also protected their interests. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki targeted the Soviet Union more than the fascists. The Yalta agreements divided the world into spheres of influence, which subsequently assisted postwar imperialism in its continued dominance.

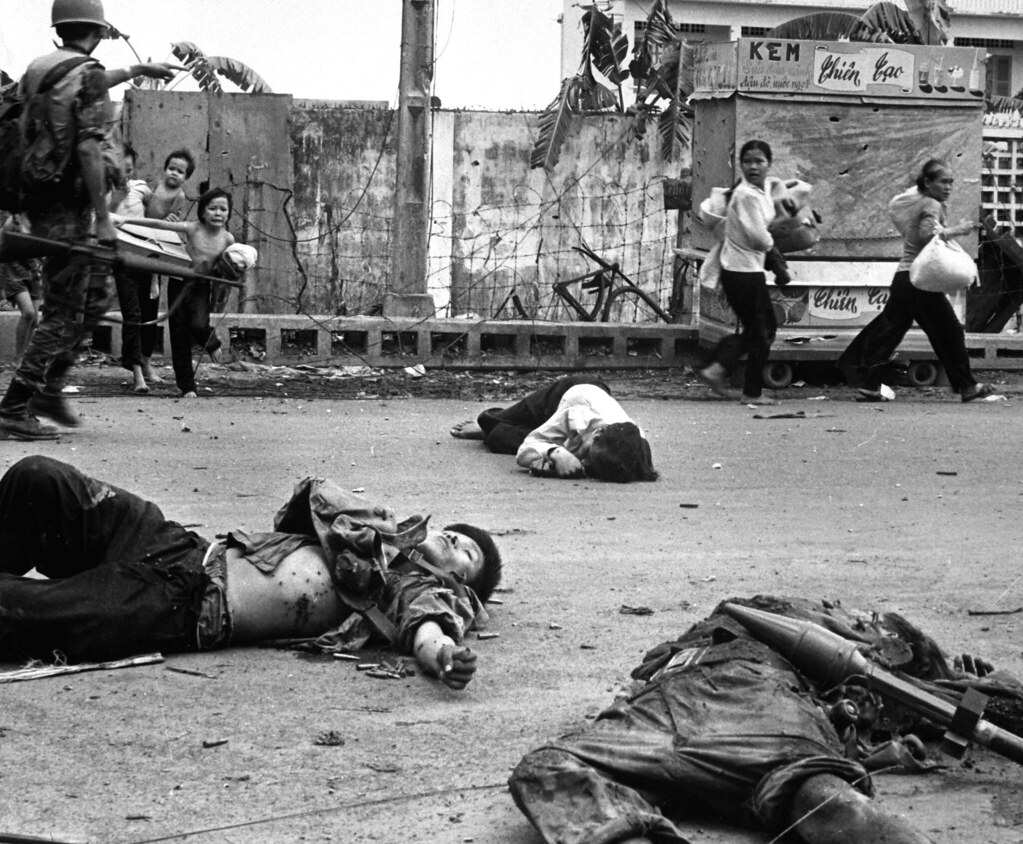

Photo Credit – Openverse

World War II was the culmination of the crises caused by World War I. In spite of an antifascist rhetoric, World War II failed to resolve the crises that were hovering around the world. Ernest Mandel observed that, “In that sense, the Second World War indeed solved nothing, i.e., removed none of the basic causes of the intensifying crisis of survival of human civilization and humankind itself. Hitler has disappeared, but the tide of destructiveness and barbarism keeps rising, albeit in more variegated forms and a less concentrated way (if World War III can be avoided). For the underlying cause of that destructiveness remains. It is the expansionist dynamic of competition, capital accumulation and imperialism increasingly turned against itself, i.e. boomeranging from the ‘periphery’ into the ‘centre’, with all the destructive potential this expansion and self-assertion harbors in the face of growing resistance and defiance from millions, if not hundreds of millions, of human beings.” ( The Meaning of the Second World War).

4. The Vietnam War (1955–1975): Anti- Imperialist War

The war in Vietnam was a struggle for the freedom of the nation. It was not an imperial war but an offensive by the United States against the will of the Vietnamese people to be free. This war began amidst a prolonged struggle against French domination, which intensified after Vietnam was divided in two based on the Geneva Accords in 1954 and then evolved into a brutal struggle against American domination.

The North Vietnamese government and the National Liberation Front (NLF) aimed to unify the nation and achieve independence from foreign control. Nothing is more precious than independence and freedom. While Hanoi’s leadership may not have adhered to revolutionary socialist ideals of a Marxist nature, the significance of the war remained profound.

Photo Credit – Openverse

The actions of American imperialism—including the use of chemical weapons, the killing of numerous civilians, and the display of systematic brutality—revealed the hypocrisy underlying its ‘democratic’ facade. Furthermore, the Tet Offensive of 1968 demonstrated that the American military were not invincible, sparking antiwar movements worldwide.

Marxists supported the Vietnamese cause while maintaining independence from their Stalinist leadership. Trotskyists argued that proclaiming ‘Victory to the NLF’ did not equate to endorsing the political aims of the National Liberation Front; rather, it was an expression of solidarity in the struggle against imperialism. The war emerged as a symbol of resistance for the international left and played a role in inspiring radical movements across the U.S., Europe, and Latin America.

IMPERIALIST WAR AND CAPITALIST CONTRADICTION

Imperialist wars in the contemporary era are characterised by inherent contradictions, often culminating in revolutionary upheaval after the conflict has concluded. The capitalist ruling class typically requires mass mobilisation, conscripted military service, and substantial taxation to sustain wars that serve their interests indirectly. To address this contradiction, all belligerent states engage in misleading representations of the people’s will to gain broad support. The claim, ‘we never wanted war,’ encapsulates this central falsehood. An unprovoked attack forced war on us; we are acting solely in self-defence. In the eyes of the populace, each warring faction presents itself as a defender of its sovereignty. It is crucial for socialists to carefully dismantle these falsehoods and expose the imperialist forces at play among the warring nations.

The recognition of the aggressor can shed light on the falsehoods propagated by state institutions and provide deeper insight into the political motivations behind a war. However, the forces that drive warfare extend beyond the simplistic labels of aggressors and defenders. At the most fundamental level, the question arises, who initiated hostilities? In any conflict, both parties endeavour to attribute blame for the war to their opponent, seeking to portray their actions as entirely defensive. The aim is to manipulate public perception, creating the impression that the warfare is a justifiable response to an unwarranted attack.

A clear case of such a phenomenon is the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which took place in August 1964 and marked the beginning of the Vietnam War. The United States contended that North Vietnamese forces attacked two American ships in international waters. Consequently, this assertion resulted in the unanimous approval (416-0) of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution by the U.S. House of Representatives, thereby granting the government the authority to take all necessary measures to “defend Southeast Asia against Communist aggression.” Subsequent revelations from the Pentagon Papers revealed that President Johnson had draughted the resolution several months prior and was simply awaiting an excuse to present it to Congress, using the reported attack as a pretext. Moreover, the Pentagon Papers disclosed that U.S. ships, namely the Turner Joy and the Maddox, were engaged in espionage and other covert activities along the coast of North Vietnam. It remains unclear whether the North Vietnamese military actually attacked the ships. Even if such an attack did occur, the incident offers little information regarding the underlying causes of the conflict or the motivations behind the so-called ‘aggression’.

A more sophisticated tactic for framing the conflict as defensive involved the decision to commence the U.S. air campaign against North Vietnam in February 1965. While the official announcement of the start of the bombing was made that month, the U.S. government had been preparing for this strategy several months prior. President Johnson and his administration instructed the Joint Chiefs of Staff to develop a plan called ‘provocative engagement,’ which aimed to elicit a reaction from North Vietnam in response to U.S. actions. This plan included operations intended to annoy North Vietnamese forces until they retaliated, thereby enabling the United States to justify the initiation of bombing under the guise of a defensive reaction to Communist aggression in South Vietnam.

Even with the United States’ efforts to establish a pretext for military involvement, the political nature of the war would have remained inherent, irrespective of who the initial aggressor was. Should North Vietnam have been the aggressor, the conflict would still have represented a just cause for national liberation on their part and an imperial act of aggression from the United States. The fundamental political dynamics underpinning the war would have persisted. When the entity that initiates hostilities possesses morally justifiable political aims, it becomes our responsibility to support them, even if this entails backing what appears to be an ‘aggressive’ policy in the pursuit of objectives such as national liberation.

It is essential to examine the defensive rhetoric employed by competing imperial powers seeking to sustain or reconfigure their imperialist alignments. In the context of inter-imperialist conflict, distinguishing between the aggressor and the defender becomes a futile exercise. The fluid alliances among imperialist powers render such dichotomies largely irrelevant. While identifying the aggressor may reveal the degree to which a government is concealing the ostensibly ‘defensive’ nature of its military intervention and may offer insights into its imperialistic ambitions, it does not provide the crucial understanding of the political forces driving the conflict.

Revolutionary Defeatism and Internationalism

The Marxist conception of war is grounded in the principles of international workers’ solidarity and the theory of revolutionary defeatism within imperialist nations. Lenin articulated this perspective by stating, “During a reactionary war a revolutionary class cannot but desire the defeat of its government.” (The Defeat of One’s Own Government in the Imperialist War, 1915). Thus, the aim is not to seek peace at any cost; rather, it is to transform imperialist wars into localised conflicts—specifically, to convert wars between nations into class struggles. The focus is not merely on achieving peace within capitalism but on igniting a revolution by leveraging the inherent contradictions of the system. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels demanded “Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution.” War exposes the fundamental failings of capitalism; consequently, Marxists must exploit these deficiencies to accelerate its downfall. In conclusion, Marxist approach war not with naive notions of peace or blind militarism but through a lens of thoughtful, historical, and class-based analysis. From the democratic revolutionary wars of the bourgeoisie to the liberation struggles of the oppressed, from the trenches of Verdun to the streets of Gaza, the prevailing vision is that of the international working class—its demands, its freedom, and its future revolution.

Editorial Board Member of Alternative Viewpoint