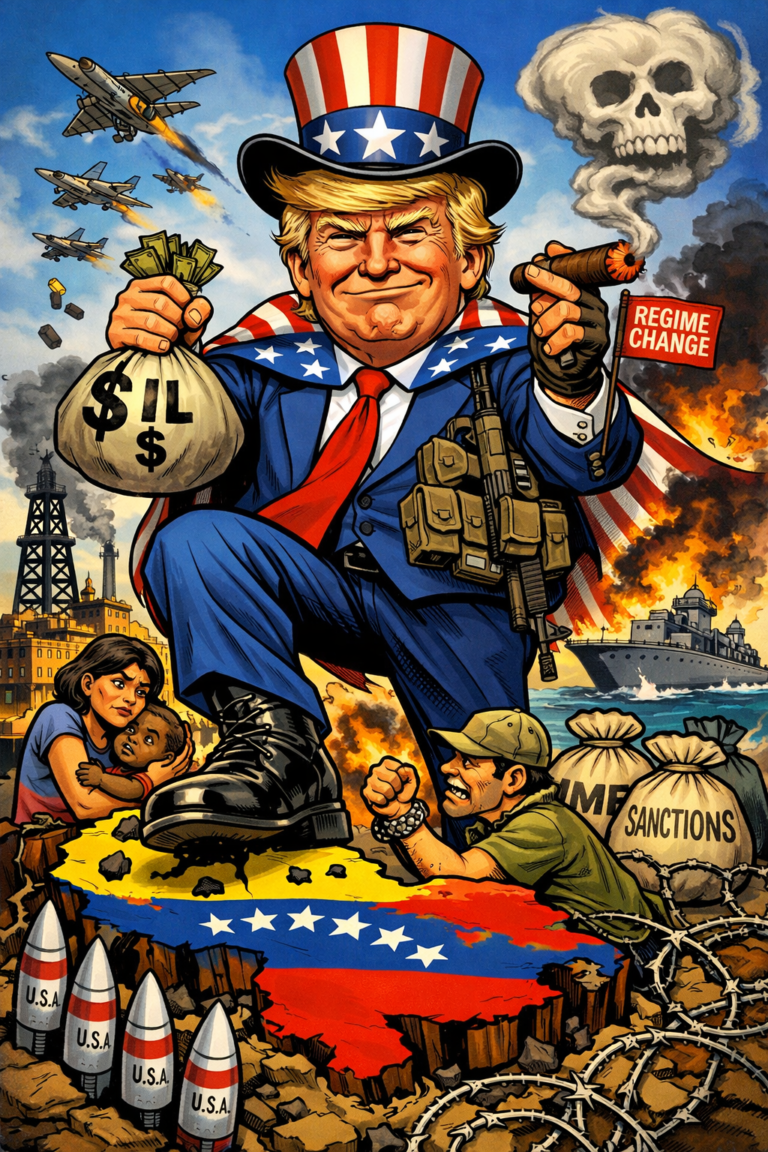

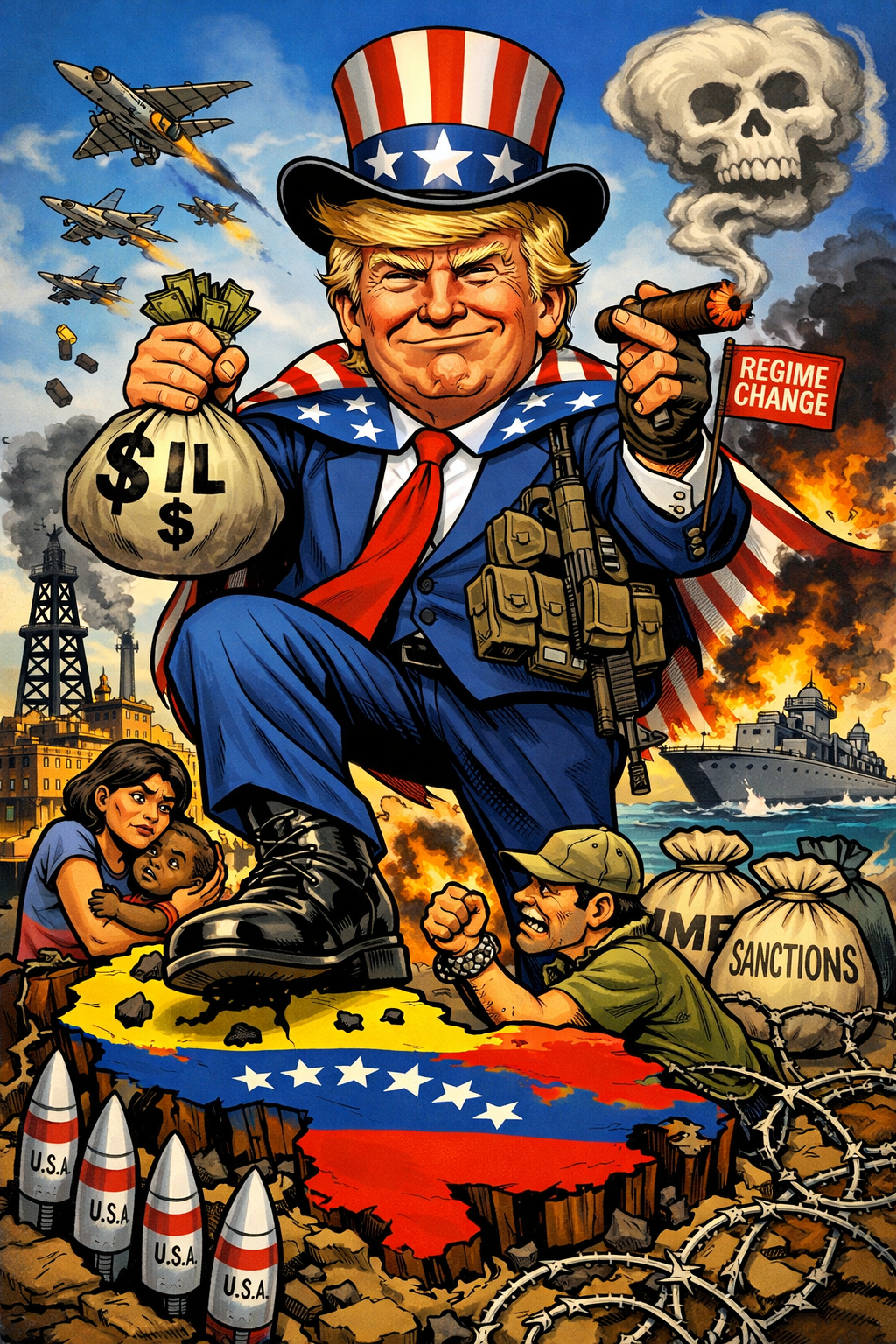

What the United States has done to Venezuela over more than a century cannot be understood as a series of isolated policy mistakes, excesses, or partisan deviations. It is best understood as a coherent imperial strategy—one that adapts its methods over time but never abandons its core objective: ensuring that Venezuela’s immense natural wealth serves foreign capital rather than its people.

From gunboat diplomacy and dictatorships to sanctions, mercenaries, and open military abduction, the form has changed, but the logic has not. Venezuela’s crime has never been authoritarianism, corruption, or mismanagement in isolation. Its unforgivable offence has been insisting that oil—a resource central to global capitalism—belongs first to Venezuelans.

Empire Begins with Structure, Not Intentions

The United States did not “become involved” in Venezuela out of concern for democracy or stability. Its involvement emerged alongside the consolidation of US capitalism as a global system. The Monroe Doctrine was not a defensive doctrine; it was an announcement of ownership. Latin America was declared a zone where sovereignty would exist only insofar as it did not interfere with US economic priorities.

When Venezuelan oil was discovered on a massive scale in the early 20th century, the country was rapidly absorbed into this imperial order. Juan Vicente Gómez’s dictatorship was not an anomaly; it was the preferred political form for extraction. Oil companies and foreign investors tolerated and supported Gómez’s brutality—torture chambers, political prisons, and enforced silence—because it guaranteed predictability.

For ordinary Venezuelans, such policies resulted in generations of dispossession. Oil wealth was syphoned off, while poverty, illiteracy, and exclusion persisted. The state’s primary function was to police the population rather than to serve it.

This context is deliberately overlooked by imperial narratives that evoke nostalgia for “pre-Chávez Venezuela.”

The Bolivarian Revolution as a Material Threat

When Hugo Chávez was elected in 1998, he did not simply introduce a new political style. He disrupted a material arrangement that had governed Venezuela for nearly a century. By reasserting state control over PDVSA and redirecting oil revenues toward social needs, the Bolivarian project altered who benefited from Venezuela’s most valuable resource.

People experienced this shift not in abstract ideological terms, but in their everyday lives. Clinics began to appear in neighbourhoods that were previously devoid of doctors. Literacy campaigns reached adults who had been excluded from education their entire lives. Housing programmes replaced informal settlements with permanent homes. Energy cooperation extended beyond Venezuela’s borders through Petrocaribe, offering relief to other Caribbean nations historically trapped by fuel dependency.

These changes did not abolish class conflict or eliminate inequality. But they demonstrated something far more dangerous to imperial power: that an alternative development path was possible within electoral politics.

That example had to be destroyed.

Assassination Conspiracies and Sovereign Kidnapping Operations

As direct overthrow proved politically costly, US policy increasingly shifted toward methods that blurred the line between coercive diplomacy and outright criminality. Formal invasion was not as prominent during this phase as a combination of lawfare, covert action, and tolerated mercenarism aimed at undermining Venezuelan sovereignty.

The most widely documented episode was the 2020 Gedeón operation, in which former US special forces personnel were involved in an attempt to capture President Nicolás Maduro and trigger an internal collapse. Subsequent legal proceedings in the United States confirmed the participation of private security contractors, while investigative journalism revealed the porous boundary between freelance adventurism and unofficial regime‑change efforts. Although the operation failed, it demonstrated how far the threshold of acceptable intervention had already shifted.

Alongside these actions, US authorities escalated legal and financial warfare. Criminal indictments, public bounties, and asset seizures reframed Venezuelan officials as transnational criminals rather than political adversaries. The purpose was not adjudication but delegitimisation. Fiat criminalises sovereignty, making its violations appear less like aggression and more like enforcement.

The cumulative effect was not a singular, dramatic rupture but rather a gradual erosion of international norms. Threats of assassination, abduction, or indefinite detention—whether carried out or merely indicated—functioned as a form of constant pressure. In this context, the real danger to Venezuela was not any specific plot but rather the precedent being set: that powerful states might openly consider extraordinary violence against elected leaders of weaker states without facing legal repercussions.

Destabilisation as Policy, Not Reaction

The 2002 coup attempt against Chávez was an early signal that the United States would not accept even moderate limits on corporate access to oil. The speed with which Washington recognised the coup regime and the silence surrounding its suspension of democratic institutions revealed how hollow its official commitments to democracy were.

When popular mobilisation overcame the coup, US policy shifted rather than retreated. Opposition funding increased. Media narratives hardened. Venezuela was reframed from a sovereign state pursuing redistribution into a “threat” that required containment.

Sanctions became the preferred weapon because they allowed immense suffering without the political cost of visible invasion. These measures did not specifically target the elite. They targeted key aspects of daily life such as imports, financial transactions, medical supplies, food distribution, and currency stability.

The result was predictable. Hyperinflation was not a natural calamity; it was deliberately engineered. Blocking payments, freezing accounts, and confiscating assets exacerbated shortages, which were not merely administrative failures. Every empty pharmacy, every closed factory, and every family that had to move became proof in a propaganda campaign that blamed the victim for the crime.

Human Cost as Acceptable Collateral

One of the most revealing aspects of the sanctions regime was how openly US officials acknowledged civilian suffering while dismissing it as necessary. Deaths from lack of insulin, dialysis interruptions, and untreated cancer were framed as unfortunate but unavoidable. In reality, they were part of the pressure mechanism.

This is where imperialism sheds any remaining moral pretence. Maintaining a policy despite clear evidence that it kills civilians is not accidental—it is instrumental.

For Venezuelans, the situation translated into years of constant uncertainty. Parents rationed medicine. Elderly people chose between food and treatment. Entire communities lived under the psychological weight of economic siege while being told internationally that their hardship was proof of their own political failure.

Criminalisation of Leadership and the Normalisation of Lawlessness

As sanctions failed to produce submission, US policy escalated into outright illegality. Public bounties on Venezuelan leaders, collaboration with mercenaries, and repeated assassination attempts crossed a threshold rarely acknowledged in mainstream discourse.

These actions matter not because of who the targets are but because of what they normalise. If a powerful state can openly plot the murder or kidnapping of foreign leaders without consequence, international law becomes a tool applied only to the weak.

The 2026 seizure of President Nicolás Maduro was not a rupture from prior policy. Years of narrative preparation culminated in the delegitimisation of Venezuela’s sovereignty in Western discourse. Imperial fiat’s labelling a leader as a criminal justifies any action against him.

Oil, Again: The Unchanging Motive

Despite all rhetorical shifts, oil remains the central axis of US aggression. The insistence that nationalisation constitutes “theft”, the rapid reentry of foreign firms following intervention, and the language of occupation being “repaid” through extraction expose the invasion’s economic core.

The issue is not about governance quality. Countries with far worse human rights records face no such treatment if they remain compliant. Venezuela’s fate was sealed the moment it asserted that oil revenues should fund public life rather than corporate balance sheets.

But Oil is not the only motive

The argument challenges claims that Venezuelan oil would be an immediate economic windfall for the United States. While Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven reserves, translating those reserves into profit is neither simple nor quick. Years of underinvestment, corruption, and political instability have badly damaged oil infrastructure, requiring enormous capital just to restore basic operations. Most of the oil is extra-heavy crude from the Orinoco Belt, which is technically difficult and expensive to extract and refine, sharply limiting profitability even for major energy firms.

Global conditions further undermine the promise of easy gains. By the mid-2020s, oil markets face oversupply, weak demand growth, and accelerating energy transition pressures. Prices remain low, margins are tight, and Venezuelan heavy crude is especially uncompetitive. Reviving production would require hundreds of billions in long-term investment, making it a risky, uncertain project rather than a quick revenue source.

Oil extraction is also inseparable from politics. Maintaining production would demand sustained military and administrative control to manage labour, suppress resistance, and protect infrastructure, turning oil into a coercive political process rather than a purely economic one.

As a result, Venezuelan oil functions primarily as a geopolitical tool. Control over reserves offers strategic leverage, particularly against rivals like China, and symbolically reinforces U.S. regional dominance. Rhetoric about “our oil” obscures motives rooted in power, control, and subordination. Anti-imperialist strategy must therefore prioritise sovereignty, social power, and popular mobilisation over narrow resource calculations.

Venezuela as Warning and Possibility

Imperial violence against Venezuela serves two purposes. First, it punishes a specific country for defiance. Second, it warns others not to follow the same path. The message is simple: elections will be respected only if their outcomes align with imperial interests.

Yet Venezuela also offers another lesson. Even under extraordinary pressure, people organised, resisted coups, maintained social programs, and defended the idea that national wealth should serve collective needs. Sanctions or military raids cannot erase that legacy.

A clear pattern emerges from various sources, such as academic research, UN reports, declassified documents, investigative journalism, and even some admissions by US officials. Venezuela has been punished not for a few bad policies but for taking control of its oil resources and insisting that this important asset serve domestic social needs instead of foreign capital. The sanctions weren’t meant to make governments more democratic; they were meant to make life harder for people, stop the flow of money, and break up civilian life. Democratic results were only accepted if they led to governments that were willing to work with outside economic interests. International law was used when it was convenient and ignored when it got in the way of imperial power.

We severly critique the Maduro regime for its anti dmeocrtaic and authoritative measures but to stand agianst UG imperialism we do not require ideological loyalty to any Venezuelan leader. They follow the accumulated record of policy, practice, and consequences. Venezuela’s tragedy is not that it tried something different and failed. It is that it tried something different at all—within a world order that reserves sovereignty for the powerful and discipline for everyone else. That is why Venezuela’s experience continues to resonate far beyond its borders.

Organiser of BDS Kolkata